Semiconductor chips help power the modern digital economy. As artificial intelligence (AI) technologies grow and start to reach the marketplace on a broader scale, large volumes of sophisticated semiconductor chips will be required. A new digital product from MacroPolo breaks down the AI chip supply chain, including which nations are angling for AI chip ascendancy. In a new interview, MacroPolo Senior Fellow Neil Thomas discusses the “Supply Chain Jigsaw” product, the future of AI chip production, how China is striving to expand its domestic semiconductor industry, and more.

Semiconductor chips help power the modern digital economy. As artificial intelligence (AI) technologies grow and start to reach the marketplace on a broader scale, large volumes of sophisticated semiconductor chips will be required. A new digital product from MacroPolo breaks down the AI chip supply chain, including which nations are angling for AI chip ascendancy. In a new interview, MacroPolo Senior Fellow Neil Thomas discusses the “Supply Chain Jigsaw” product, the future of AI chip production, how China is striving to expand its domestic semiconductor industry, and more.

What led you to include AI chips as part of the Supply Chain Jigsaw?

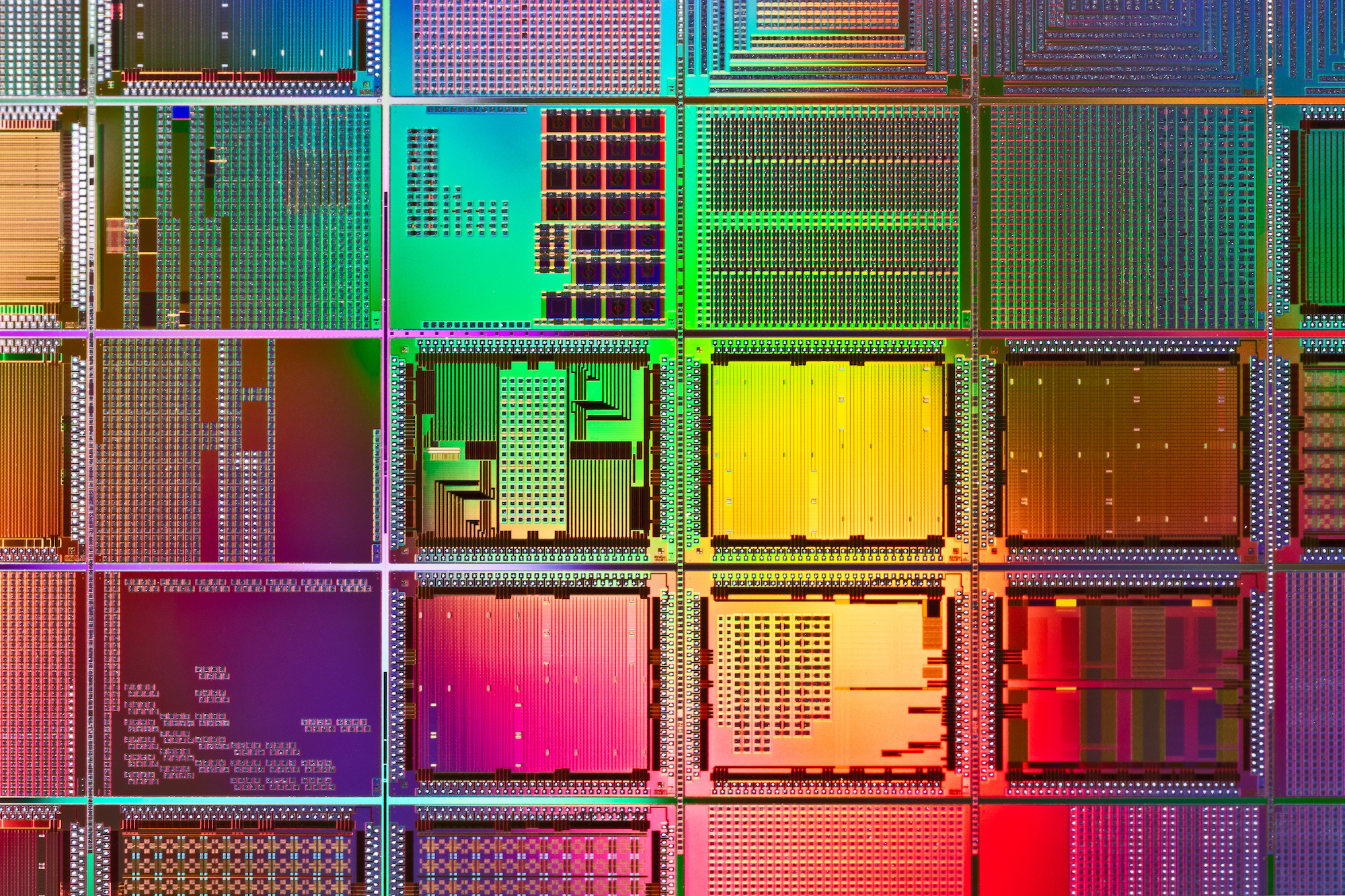

Semiconductor chips are the engines of our digital lives. Fitted with billions of electronic transistors that constitute elaborate integrated circuits, these chips power everything from laptops and mobile phones to smart TVs and automobiles. And the next frontier in this ~$450 billion industry is chips that support AI technologies. These “AI chips” are forecast to comprise up to 20% of the total semiconductor chip market by 2025.

What were the main resources you turned to while researching AI chip supply chains? What was the research process?

A great value-add of the “Supply Chain Jigsaw” digital project is that it synthesizes the data stories produced by a wide range of existing sources, including official documents, research reports, media articles, and industry data. Damien (Director, MacroPolo), Houze (Research Fellow, MacroPolo), and I first brainstormed how to structure the product that we thought was missing from the intellectual landscape; then we each drafted separate sections of the product before coming together to edit down to the final version.

More so than other tech “commodities,” semiconductor chip production seems to be often intertwined with geopolitical competition and national security. What explains this pattern? With such global supply chains, what can nations do to prevent geopolitical tension from disrupting chip production?

Semiconductor chips are crucial ground over which the competition for technology leadership will be fought as they are highly-complex products that underpin modern electronics. Tensions around reducing costs, mitigating risks, and investing in innovation will only deepen with time. Therefore, it is imperative for governments and businesses to understand the complex global interdependencies of semiconductor supply chains.

You posit that the diversity in AI chip designs opens the door for new market entrants. Where around the world are AI chip supply chains growing?

AI chips are still very much an emerging sector, and so we don’t know for sure who will develop the best AI chips going forward. The most promising design firms are located primarily in the US and China, but there’s also activity in other countries like South Korea and the United Kingdom.

Recently, there were reports that a chip factory in Wuhan was able to stay open despite the city’s lockdown. What does that suggest about China’s AI chip priorities?

In January, when China locked down Wuhan, a city of 11 million, to slow the spread of COVID-19, medical workers were exempt from this confinement. But they weren’t the only ones: authorities also reserved special train carriages for semiconductor experts brought in to keep the factory humming at Yangtze Memory Technologies Co. This stunning exemption to a stringent quarantine shows the importance that Beijing attaches to building a strong and self-reliant industry for semiconductor chips.

The Trump administration is currently weighing new restrictions on companies that use US-made equipment to produce chips for Chinese firms like Huawei. If implemented, what effect would these regulations have on the industry?

China’s weaker presence in these segments of the supply chain has prompted some to argue that now is a good time to shut out its companies. But that assessment is incomplete because it neglects China’s voracious appetite for foreign chips. The country is a global hub for electronics manufacturing and the most important end-use market for US semiconductor firms. That money is crucial in an industry that demands an exceptionally high spend on capital and R&D—around 30% of total revenue—to sustain innovation leadership. Without a stable of foreign customers, of which China is by far the largest, many of these chip firms may struggle to maintain their edge over state-backed Chinese competitors.

China has sought to boost its domestic production of AI chips. How do you see China’s market share growing in the future, if at all?

China is still playing catch-up when it comes to the domestic production of high-end semiconductors, so I would expect China’s market share to continue to grow. However, it’s an open question as to whether Beijing’s innovation push will be able to catch up to the manufacturing breakthroughs that are achieved by the world-leading Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation.

What major changes, if any, do you expect to occur in the supply chain for AI chips over the next decade?

Making granular forecasts for such a complex and still emergent industry is difficult. Still, it’s likely that both East Asia and the US will remain significant epicenters of production and innovation.

For further analysis of the AI chip supply chain, read Neil Thomas’ latest commentary. Catch up on the latest from the Paulson Institute’s in-house think tank at MacroPolo.org.